Reviews out of AFI FEST

AFI FEST 2014

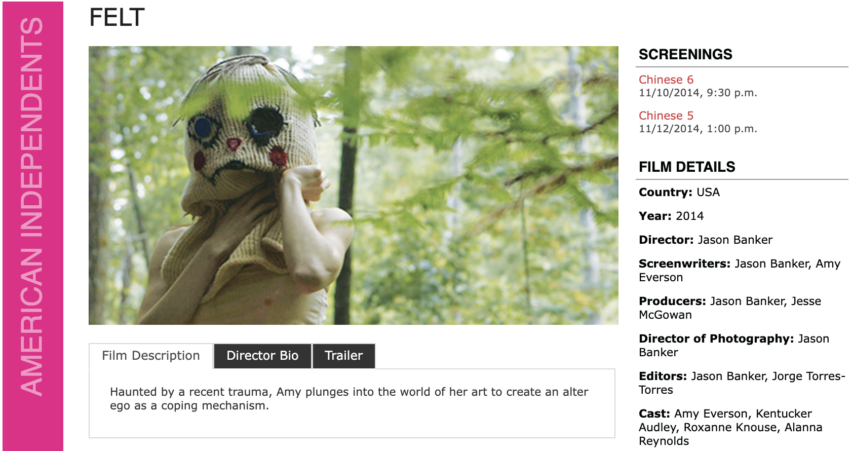

Amy, a San Francisco artist, is haunted by a recent trauma that was inflicted by men in her life. As she veers dangerously close to a complete emotional and psychological breakdown, she plunges into the world of her art as a coping mechanism. She re-appropriates the male form by creating an alter ego that assumes power and domination. When Amy meets Kenny, a seemingly nice, down-to-earth guy, she decides to open herself up to him, hoping he can restore her faith in mankind. Blurring the line between narrative and documentary, director and co-writer Jason Banker uses the real-life art and experiences of co-writer and actress Amy Everson to craft a feminist film, which confronts rape culture and the micro-aggressions that women face on a daily basis in male-dominated spaces. —Jenn Murphy

Jason Banker’s narrative feature debut, TOAD ROAD, premiered at the 2012 Fantasia Film Festival, where it won Best Director and Best Actor. His follow-up feature, FELT, won Best Actress at Fantastic Fest 2014.

IndieWire / Rachel Bernstein

Amplify Acquires Docu-Narrative ‘Felt’ To Help Shed Light On Rape Culture

Amplify says “You’ve never seen a film like this before”

Amplify has just acquired the North American rights for Jason Banker’s character study film “Felt” in a deal organized by Nate Bolotin and Mette-Marie Katz of XYZ Films (on behalf of the filmmakers) and Dylan Marchetti (on behalf of Amplify). The film follows the real life of co-writer and protagonist Amy Everson, who received a best actress award at Fantastic Fest for her performance.

Banker explores the psyche of a young woman who attempts “to overcome both a past trauma and the subtle aggressions she experiences daily from the men in her world by immersing herself in her art. By-appropriating the male form into an unpredictable alter-ego, she may be pushing away her friends, but the power and domination she feels is the only thing that finally may allow her to heal,” according to Amplify’s synopsis.

The film blends the documentary form and fictional narrative through Banker’s stylized approach. Amplify’s Dylan Marchetti described the film as something that “defies genre in the absolute best way. It’s a baseball bat to the face of rape culture, and that’s something that’s sorely needed. It’s cliche to say ‘I’ve never seen a film like this’, but I’ve never seen a film like ‘Felt’ and neither have you.”

The co-writer and central subject of the film, Amy Everson, explained that the project “is a deeply personal film and the way it’s resonated with people highlights the importance of having serious discussion about how society treats women. I am grateful it’s being distributed by a company that understands this and wants to spread awareness with us.”

“Felt” will be released to U.S. and Canadian theaters in April 2015, with a digital/home video release to follow.

IndieWire / Ryan Lattanzio

Amplify has acquired North American rights to director Banker’s ‘Toad Road’ followup based on the disturbing real-life experiences of cowriter and star Amy Everson.

Fantastic Fest best actress winner Amy Everson plays a traumatized artist who slips into elaborate fantasies to escape her troubles with men, making mischief in the wilds of her imagination under the guise of a bluntly Freudian yet ingeniously crafted alter-ego.

“Felt” sends even a rape revenge movie like “I Spit On Your Grave” running with its tail between its legs as Amy’s psychosexual paranoia produces acts of malice not easily shaken. The film is currently stirring audiences at AFI Fest in Los Angeles and will be released by Amplify (“Kumiko the Treasure Hunter”) in April 2015, with a digital/home video release to follow.

Cinematographer turned director Jason Banker first raised eyebrows in 2012 with “Toad Road,” a psychedelic portrait of teenage burnouts whose drug-taking fuels their pursuit of some mythological version of hell in Pennsylvania.

Fangoria / Samuel Zimmerman

Amplify Takes Jason Banker’s Stunning “FELT” for Spring 2015

Challenging and revelatory, Jason Banker’s second feature FELT is set to leave you silent and stunned this spring.

Having world premiered to great acclaim this past September at Austin’s Fantastic Fest, FELT is the next step in Banker’s exciting voice (following the unsettling TOAD ROAD), one that smashes doc and fiction together as he builds narrative around a real life subject. Enter Amy Everson, an artist who Banker chronicles and in the process reveals a great talent. Together the two visualize and tackle an overtly and overwhelmingly aggressive world for women. Ours. Having just played AFI Fest in Los Angeles, Amplify has announced its acquisition of FELT and an intended release in April 2015.

Directed, produced, co-written, and shot by Banker FELT stars Amy Everson in a breakout performance as a “young woman trying, and almost succeeding, to overcome both a past trauma and the subtle aggressions she experiences daily from the men in her world by immersing herself in her art. By re-appropriating the male form into an unpredictable alter ego, she may be pushing away her friends, but the power and domination she feels is the only thing that finally may allow her to heal. When she meets Kenny (actor/filmmaker Kentucker Audley), she slowly opens herself up to him, hoping to have her faith in men restored. Completely blurring the line between narrative and documentary, FELT doesn’t just point a finger at rape culture; it takes a full on swing at it that audiences will be hard-pressed to shake off.”

“FELT is the kind of film that defies genre in the absolute best way,” said Amplify’s Dylan Marchetti. “It’s a baseball bat to the face of rape culture, and that’s something that’s sorely needed. It’s cliché to say ‘I’ve never seen a film like this’, but I’ve never seen a film like FELT, and neither have you.”

“From the beginning I knew that Amy’s unique and powerful story needed to be told,” said director Jason Banker. “It was important that FELT ended up being released by a company that understands its pressing cultural relevance. I am indebted to Amplify for being that company.”

“FELT is a deeply personal film, and the way it’s resonated with people highlights the importance of having a serious discussion about how society treats women,” said co-writer and star Amy Everson. “I am grateful it’s being distributed by a company that understands this and wants to spread awareness with us.”

For more on FELT, I wrote of its merits and tremendous effect in my Fantastic Fest report here. If you’ve yet to see TOAD ROAD, it’s streaming on Netflix and Hulu now.

The Moveable Fest / Stephen Saito

AFI FEST ’14 INTERVIEW: AMY EVERSON AND JASON BANKER ON WEAVING AN INDELIBLE EXPERIENCE WITH “FELT”

On their stirring psychological study of a young woman confronting abuse with her art.

Amy Everson wasn’t feeling well as “Felt” came close to wrapping production. To say she gave her all to the film was an understatement, drawing upon a deeply painful personal past for the story of a young woman who keeps the world at arm’s length by creating costumes for herself that allow her to be someone else. But after lending her unique and inventive crocheted creations – often related to genitalia – to the film, not to mention some of her experiences and even her name, Everson was spent, feeling “shaky” and unable to eat because of a mysterious bug. Still, whatever was left, she was ready to give.

“She was a trooper, because I knew she was hurting,” recalls Jason Banker, who directed “Felt.” “When somebody is not feeling well, you don’t want to force them to do something, but she stuck with it…and some of the best things that she does in the film, I think, are in that final day’s worth of shooting.”

There’s no doubt that such commitment was necessary to make “Felt” as extraordinary as it is – for her troubles, Everson was honored with a much-deserved Best Actress Award at Fantastic Fest where the film premiered earlier this fall. But what’s beautiful about the film is how Everson and Banker combine their talents to create a one-of-a-kind horror film that’s intimate yet bold, offering an arresting study of recovering from psychological trauma at the hands of men that’s as visually potent as it is cerebrally stirring, particularly once Amy is shown to open herself up to the possibility of finding a connection with someone she meets at a bar (Kentucker Audley).

Shortly before the film made its West Coast debut at the AFI Fest in Los Angeles, Everson and Banker, along with Roxanne Lauren Knouse, who appears in the film as a model who befriends Amy, described how their own watering hole encounter led to the making of “Felt,” the immersive filmmaking process that led to such an indelibly moving experience, and what it’s been like to have people share their own experiences after seeing the film.

How did this collaboration come about?

Amy Everson: We just randomly met at a club and I introduced Banker and his filmmaker friend to some of my art.

Jason Banker: [Amy] was telling us about her art and we went back to her place. She took us through all the costumes and we were blown away. Me and my friend, who is a director as well,

just randomly shot something with her that we turned into a music video.

Amy Everson: Yeah, it wasn’t really intended to be a music video. I was just putting on some random costumes that they shot a bunch of footage.

Jason Banker: Then, a year-and-a-half went by and I kept thinking about her and making something more than just this video. One day, I just called her and asked, “Do you want to make a film with me?” She wanted to. That’s how it happened.

Amy, why was this something you wanted to do?

Amy Everson: I really liked [Jason’s] work from the music video and he basically proposed it as, “If you wanted to say anything to the world, what would it be?” I never really felt like I had a story worth telling. This story wasn’t even at the forefront of my mind. It just unfolded based on Banker following me with a camera and learning more about my life and how I interacted with people. I was at a point in my life where I was aimless and voiceless, and I was willing to just go along for the ride. I’m glad I did.

Was the art developed specifically for the film or did it already exist?

Jason Banker: I’d like to say it was made for the film, but it totally wasn’t. It was her world and when she opened it up and let us in to see what she was doing, it just resonated with me visually. As a filmmaker, you’re always looking for somebody that inspires you to want to make something, at least I do. Her artwork was super compelling, so I knew I had to do something with her.

Was it interesting for Amy to see how that art of yours fit into a narrative?

Amy Everson: Absolutely. We shot over a year or so, and [Jason] would fly out to San Francisco and shoot a little bit here and there. I really didn’t see where any of it was going. We had actors, of course, and there were scenes that we created and we played out, but in terms of exploring what my art meant to me, I don’t think I really had a clear understanding until I started getting in touch with “Why do I do it?” and how it fits into my life and how I interact with people. Even after seeing the end product and hearing people’s analysis [of it], it’s really hard to see objectively what it all means. For me, I’m just watching myself, like a home video and it’s through other people that I’m like, “Yeah. That is what it’s about.” I’m glad it makes sense.

If you weren’t that self-conscious, did that make it easier to act naturally on camera?

Amy Everson: I’m not sure if it’s harder or easier.

Jason Banker: It was. We started it with just [Amy] being herself. That’s the way I like to start as a documentary where you’re not interrupting anything that’s really going on and just let the person just be who they are. We’ll use a lot of that stuff, but then we slowly introduced what could be a story. Then there were scenes where she had to adopt a different persona for some of it, but it was a slow process. It wasn’t like, “Okay, now you’re going to act.”

Amy Everson: It’s a good introduction because Banker makes me feel comfortable in front of the camera. Then it just comes naturally.

Jason Banker: I knew she could pull it off because when we shot this music video, she was great on camera. I wasn’t worried. It was just putting in the work to go further with it.

Roxanne, how did you get involved in this?

Roxanne Knouse: Jason asked me to work with him a while ago, but it didn’t really work out and when he explained this project that’s going on with Amy, I really got behind it when I found out more and more what it’s about. I was really interested to see what was going on with her and her story. She seemed like a real person and [the subject] is something hugely important in my life as well, and wanted to showcase because I don’t think it’s really showcased that much in films. I thought [Amy] was a great voice to take that bull by the horns and do it up.

One of the great things Jason does as his own cinematographer is to shift perspectives within a scene or focus on different elements with the frame. Does that take a certain amount of planning or do you just do what’s instinctual?

Jason Banker: I prefer not to plan anything. That’s maybe my biggest flaw and my biggest strength at the same time. At certain times, Amy was like, “What are we even doing?” But I can see what’s working. I’m figuring it out as I’m shooting it, which is what the adrenaline rush for me is. It’s like, “We don’t have a plan. We’re going to throw elements together and see how they interact.” The scene in the hotel with the Australian guys was completely [improvised]. We just went to the hotel and we were like, “Let’s make something happen.” To me, that scene feeds into the style of the way that I like to work. Amy is great at just working with that. Even though it may be frustrating sometimes, she always pulls off miracles. Then when Roxanne came in, she brought that too.

Amy Everson: Everybody brings a part of themselves. It’s like the stone soup where everybody brings an ingredient and it becomes a whole. Of course, there’s the main chef here, but it works.

Jason Banker: The first scene with Roxanne, I just knew that I wanted a scene with a photographer and I had my ideas about the way that it could go, but they brought something way better than I was even thinking. That’s what I love. I enjoy that conversation you have in real time about what we’re making and people being like, “Well, I have this idea…” There was a couple different versions of that scene, but the one that’s in the film was the magic.

Given the nature of the story, was it interesting to have the two main creative voices here be a man and a woman?

Jason Banker: I was totally out of my depth on many occasions making this film. But I enjoy somebody throwing something back at me. I set things up the way that I think, then the people I’m working with might say, “Oh, that’s totally bullshit.” I’ll listen to it and be like, “Okay, actually, you do have the better idea.” It was frustrating for me at times, because [Amy] would tell me I was wrong, but then there were things that I was just so happy that she inserted in the way that she did. That’s why I do give [Amy] a huge amount of credit for the voice of the film, because my voice is definitely present and it’s creating something that she didn’t realize was going to happen because she trusted me. At the same time, I was really trying to get her story out there and I wanted her to be as collaborative and as giving with that as possible. I’m really proud of the way that it worked out.

Amy Everson: Yeah. We butted heads plenty of times and we had different opinions, but that was a healthy discussion. That’s what made the film. It’s this struggle and conflict within my life that made me that much more fierce in the film. I’m dealing with someone who may not recognize immediately what it feels like to be a woman, but …

Roxanne Knouse: …is willing to learn.

Amy Everson: … is willing to learn and follow the story and document it. It’s that conversation that unfolds within the film more.

Does this film mean something different to you than when you first started it?

Jason Banker: I like not knowing necessarily what I’m going to get at the end of the day. That’s part of the reason why I’d prefer not to work with a script or really with any plan. I just wanted to discover what the film would be with [Amy]. That’s part of what I like about filmmaking is having a conversation with somebody, usually somebody who’s really lived something that they can reflect on and and say, “This is what I feel.”

Amy Everson: I had ideas when I started about what story I wanted to tell, but then as we were going along, I wasn’t sure if that story would translate. Seeing the product at the end has been completely different from what I had imagined from the beginning, but I’m glad it came out that way. During the course of filming, a lot of things were happening in my life that really blended into the story.

The reviews from Fantastic Fest elicited quite a few deeply personal responses to the film. What was it like to be embraced in this way?

Amy Everson: It’s been a huge honor because it’s a personal story, but then having people really understand and empathize and analyze it and really get what a struggle I’ve been through in my life and what a lot of women go through has been really moving because so much of our lives are built around silence and shame. For me, to have a voice and share it, then for people to say, “This is important. This is good” is just mind-blowing. The reception has been the most wonderful part of the process. Having people even approach me and say, “That really moved me personally,” and telling me about their personal stories has been an amazing experience.

Jason Banker: There is also this thing about me being a male director and telling this story that really touches women because Amy’s story and life resonated with me on a level that I don’t even know necessarily. I could connect with it and at the beginning, there was a lot of need to say, “Trust me. I’m going to do the best that I can to honor your story.” I’m just glad that it came out. To me, that’s the most important thing is that she’s happy.

“Felt” plays AFI Fest once more on November 12th at 1 pm at the Chinese 5 in Los Angeles. It will be distributed next year by Amplify.

Sound on Sight / Bo Yun Um

AFI FEST 2014: ‘Felt’ Shows the Jarring Effects of Rape Culture

It’s a rare discovery when a film can materialize the internal terror that women experience on a daily basis so disturbingly close to reality. Blurring the lines of documentary and narrative storytelling, Felt truly is a film that demands to be felt. It accomplishes its goal by penetrating the deepest, most harrowing aspects of trauma to tell one of the most powerful and jarring stories about the female experience and rape culture ever put on screen.

Director and cinematographer Jason Banker follows his 2012 debut film, Toad Road with Felt, co-written by Amy Everson who stars in the film as Amy, a San Franciscan artist recently plagued by a trauma (not explained but certainly sexual) inflicted by the men in her life. As her ordeal unravels emotionally and psychologically, she plunges herself in the world of art as a coping mechanism.

“My life is a fucking nightmare” are the first words out of Amy’s mouth, a vocal confirmation of her trauma, usually reserved for her performance art. From there, we see her as she caves in on herself, crawling so deep and beyond, it’s unknown where the real Amy starts and ends. She re-appropriates the male form by frolicking in the woods, wearing an anatomically correct muscle suit and trying to re-enact the dominance demonstrated by the men she’s encountered. But it doesn’t stop there, as she continues to embrace their stereotypical brash, lewd attitude outside of costume form. This outlet to reclaim the power taken from her by an unknown attacker is only the beginning of how her mental disintegration manifests. Witnessing her inner battle materialize in outer form further conveys the delusion and terror that Amy struggles with every day, heightening the grim realities and the harsh effects of our gender warped society.

As Amy, Everson is equally charming and quirky yet brutally dark and intense. With these contradicting polarities, Amy is a compelling character who thrives in her darkest moments. Her egg-shell thin fragility only evokes the uneasiest tensions and like a ticking bomb, she’s bound to go off with a bang! When she isn’t creating art, Amy goes on dates with grade-A assholes for reasons unknown considering the obvious or toys with photographers who primarily want to shoot female nudes by dressing up in her costume. Even as much as Amy is drowning in her palpable vulnerability, she makes bold moves and is aggressively courageous in moments of potentially looming danger. Things take a turn when she meets Kenny, a genuinely good guy. But this isn’t the type of film that caters to happy endings, and naturally with escalating jabbing tension, tragedy strikes. Still, regardless of it’s unexpected and shocking ending, it’s Everson who is at the center and keeps the film in orbit with her haunting performance.

Banker utilizes his signature documentary style to create the suffocatingly intimate and teeth-clenching uneasiness that is Amy’s nightmarish world. But this style of filmmaking goes even deeper considering it’s meta-textual underpinnings (Everson is a real life artist and all the art we see in the film is hers). Instead of resorting to a traditional art documentary, Banker’s collaboration with Everson tells a story that resonates skin deep no matter what gender. Felt is a rare gem that shows a unique female perspective trying to seize back control of her identity without preaching overt misandry. As the film proves however, it’s hard to be a woman in a man’s world.

Movie Mezzanine / Dan Schindel

AFI FEST REVIEW: “FELT”

Felt might be more vitally of the moment than any other film that people aren’t likely to see. Right now, a very necessary conversation about rape culture and the myriad ways that society is hostile to women is taking shape. Felt isn’t a piece for conversation, though. It’s an experience. It’s an unvarnished, unpretentious, and seemingly unassuming portrait of what it’s like to be a woman and feel the world crushing your throat under its heel.

Amy Everson is a San Francisco experimental artist who’s experienced sexual trauma in her recent past. In Felt, she plays… Amy, a San Francisco experimental artist who’s experienced sexual trauma in her recent past. Everson co-wrote the script for the film with director Jason Banker, contributing her characteristics, her art, and real incidents from her life to the project. The result is a queasily fuzzed line between fact and fiction. Amy (the character) is in a place of tenuous emotional stability, and the movie makes her heightened, prey-animal viewpoint vividly real. The everyday monstrosity of men who harass her in bars or on the streets is mundane yet terrifying.

Felt is about finding a way to reclaim one’s sense of power and self-security. Amy’s art incorporates felt and yarn recreations of male iconography, including many, many phalluses. She builds a suit with bulging muscles and poses in it in the sunset. She has a penis voodoo doll, and sticks a pin up its urethra. It could be too quirky or come off as shallow hipster eccentricity, but Everson sells every aspect. She is weird and offbeat, not in a cute Hollywood way, but off-balance, gritty and unsettling. She seems like the kind of person you’d inch away from if they sat next to you on the bus, despite the fact that she’s clearly in desperate need of some kind of comfort.

That empathy is the cornerstone of the film, which builds its plot, such as it is, around Amy meeting what seems to be a nice guy. Kenny (Kentucker Audley) is sweet, considerate, gentle, and almost perfect. Too perfect, even. Perfect enough that, while Amy grows to trust him, a ball of unease burrows itself deep into the audience’s collective stomach. Having established how fragile Amy’s sanity is, the movie builds spectacular dread out of waiting for the shoe to drop. #NotAllMen? #YesAllMen.

Felt is a pair of scissors thrust into the gut. If films came with trigger warnings, this one would be plastered with them. It’s not that it contains graphic depictions or even descriptions of triggering content (with one very notable exception). Rather, it makes gender-based micro-aggressions uncomfortably front and center. It uses empathy as a weapon against the audience, forcing them to confront this aspect of our culture in all its ugliness. It’s unshakeable, as it should be.

Grade: B+

The Hollywood Reporter / Justin Lowe

‘Felt’: AFI Fest Review

Writer-director Jason Banker and artist Amy Everson collaborate on a borderline bizarre psychosexual drama

Filmmaker Jason Banker’s second narrative feature relies heavily on his prior documentary experience for this disturbing portrait of a young woman struggling with the debilitating psychological effects of sexual trauma. The film’s largely improvisational style and DIY production values signal limited art house potential when Amplify releases Felt next year, with marginally better opportunities in digital formats.

As Amy (Amy Everson) tries to make a highly uneven recovery from a series of very bad relationships that may or may not have involved sexual assault (much is left undisclosed throughout the film), she attempts a variety of dysfunctional techniques to resolve the trauma. Initially withdrawing from even her roommate and best friend Alanna (Alanna Reynolds), she spends much of her entirely idle time lost in melancholic reverie, ensconced in her bedroom or aimlessly wandering the streets of her San Francisco Bay area neighborhood.

As an artist, she naturally tries to channel her efforts into one of her projects, creating homemade body suits from sheer beige material. Adding a fake phallus to her outfit, she play-acts some violent revenge fantasies alone in the depths of a redwood grove, but apparently these antics provide an insufficient resolution to her increasingly complex psychological conflicts. Unexpectedly veering in the opposite direction, she begins hanging out with Kenny (Kentucker Audley), a random guy she meets one night playing pool in a neighborhood bar. Their blossoming relationship seems to provide some stability as her behavior temporarily normalizes, but then Kenny’s own secrets threaten to push them both into risky, unknown territory.

Banker, who also produces, shoots and edits the film, refers to his collaboration with co-writer and San Francisco-based artist Everson as “docu-horror,” but the film’s verite approach never remotely achieves genre status. With predominantly improvised dialogue and performances, Felt gains scant narrative complexity from an over-reliance on a no-frills documentary style.

Although Everson’s representation of Amy’s psychological affliction demonstrates an unconvincing Freudian literalism, her increasingly bizarre artistic interpretations do manage to build some mildly escalating tension. Whether those developments possess enough significance to bestow the film with a compelling plot may depend on one’s interpretation of dramatic structure. The film’s dependence on practical locations and handheld cinematography, however, appear to be as much a budgetary consideration as a stylistic choice, but could be said to suit the material’s determined realism.

Sound on Sight / Pamela Fillion

REEL MTL: Jason Banker’s Sophomore Feature, ‘FELT’ Poignantly Tackles a Difficult Subject

How do you make felt? There are two general ways: the first is by drowning wool and then shocking it dry and the second requires poking and prodding with a needle until the wool becomes a wholly new material. Amy, whose world FELT allows us to dive into, is an artist who has crafted an arsenal of felt penises and body suits, through which she explores and escapes into alter-egos.

Much like felt, Amy has been through rough times, which have begun to unravel her:

“My life is a fucking nightmare”, Amy’s voice, tentative and cracking opens the film, “every waking moment, every time I close my eyes, I just relive the trauma. I’m never safe and I can’t even tell what’s real anymore, everything… just blurs. I don’t sleep, I don’t eat, I’m just walking through this dream … ghosts haunting me.”

FELT will ring harrowingly true for audiences who have personal experiences with trauma and ptsd: particularly those who have experienced gender-based violence. For those who haven’t, the film provides a look at the embodied consequences of violence and its destabilizing effects. As Amy tries to hang on to friendships (her friends are at the end of their ropes), all the while escaping into and through her art, she tries to establish new relationships, the pervasiveness of rape culture becomes all too clear as are the high costs of intimacy, romantic and otherwise.

The films evocative power lies in the talent of Amy Everson, who plays Amy. Everson delivers an incredible performance bringing this complicated character to life: both frail and daring, delicate and an unabashed “potty mouth”, depressed yet still humorous, creative and destructive. FELT’s Amy is constantly finding herself in hallways and transient spaces, literal and metaphorical ones, and it is in these liminal spaces, where she contemplates ways to get herself out of the predicament she finds herself in: ways to regain control. At times, friends join her in these hallways sharing their own fantasies and desires. It is in one of these hallways, where Amy begins her friendship with Roxanne, the films second most intriguing character, played by Roxanne Lauren Krause, whose time on screen feels cut short.

Carefully curating Everson’s talent and art, is Banker’s cinematography. FELT is Jason Banker’s second feature. His first narrative, Toad Road, took home the award for ‘Best New Director’ and ‘Best Actor’ at the Fantasia International Film Festival in 2012. Banker has been on my filmmakers to watch for list since then. The imagery and visuals in FELT are arresting and carefully pieced together while retaining an organic and raw component. There is here a continuation and evolution of Banker’s filmmaking style which blends documentary, genre, and art house styles into something wholly new: a fascinating hybrid. There is a distinct artistic aesthetic to the film that can lend itself to lengthy cultural studies analysis beginning with the use of Amy’s red hoodie as a signifier (index) and of course, the visual texture of her suits and crafted world. The combination and collaboration of Everson’s art and Banker’s filmic method is striking. In this genre film, there is horror on multiple levels. I, for one, find the film deeply personal, heartbreaking, and tragic.

Last but not least, one of the more influential elements of the film is the carefully chosen soundtrack featuring songs by Deaf Center, Scott Tuma, Joakim and Brambles . Indeed, sound design and soundtrack can make or break a film and for FELT, the choices were spot on. Downright haunting, the melodic pulse of the film, Deaf Center’s ‘Time Spent’ is insidious, slightly creepy, sweet yet hurting.

FELT recently was picked up for North American distribution with Amplify.

Verite / Anton Bitel

Under the radar US indies of 2014: FELT

“My life is a fuckin’ nightmare,” says Amy (the astonishing Amy Everson) in voice-over at the beginning of Jason Toad Road Banker’s Felt, as she sits at home, visibly upset, before donning a one-piece green lizard costume of her own making and venturing out into the street. “Every waking moment, every time I close my eyes, I just relive the trauma. I’m never safe. And I can’t even tell what’s real anymore.”

This is the first and last time her voice-over will appear in the film, carefully establishing a damaged interior that is not always so apparent in the brash, aggressively quirky exterior that she shows to others. Yet Amy bears deep emotional scars that we infer – without ever quite being told – have been inflicted by sexual abuse and rape going back to her childhood. Arrested and unable to break free fromher wounded state, she tries to claw back some control though fantasy, ‘dress-up’ and art.

So it is that Amy’s collection of dolls and other toys (both infant and adult) has been reconfigured into disturbing sexual tableaux in her bedroom. So it is that when she is not earning money dressed as a chicken to advertise a restaurant’s fare, she painstakingly fashions her own special outfits at home from a range of materials for semi-private exercises in role play and would-be catharsis. And so it is that she regularly discusses with (female) friends her plans for male genital mutilation and murder sprees. The question of whether she is joking or serious brings to Felt a palpable tension.

This conflict between what is real and what is fiction is woven through the very texture of Felt, which offers up in an observational style (that could almost be called ‘documentary’) aspects of Everson’s own life and past (not to mention the extraordinary costumes that she makes), while also incorporating elements of horror. Amy is set up as a real person (not unlike the actor who plays her and shares her name), but also as the heroine of a rape-revenge movie—and viewers are left to negotiate the difference in this game of identities, and to experience for themselves something of Amy’s own dissociative experience.

In the first half of Felt, we see Amy struggling through social or dating encounters with a range of men who casually introduce the language of rape into their banter, or express their gendered dominance and arrogance in other ways. The second half traces her evolving relationship with Kenny (Kentucker Audley), an unusually sensitive, respectful man who drifts into Amy’s orbit and becomes like ‘one of the girls’, promising the possibility of a new life—until a simple act of betrayal triggers something primal in Amy.

Much of the film’s focus is on the blurred lines between the sexes, as Amy, through cosplay (and shamelessly vigorous farting), makes a performance of anatomy and biological function. “Everything is qualified”, Amy complains of her status as a woman, “by the fact that you don’t have a dick”, which drives her to dress in a man suit in her alone time, complete with stubbly mask and pendulous phallus, to feel for herself how the other half lives. She also, at a pornographic photoshoot, dons prosthetic breasts and a graphically crocheted pair of vulva pants as “a celebration of the female figure.” And yet it is male genitalia that are her principal preoccupation, leading to a horrifying climax, part triumph part tragedy, stitched together from the transgressive offcuts of Sleepaway Camp, Nekromantik 2, May and Julia.

Whenever she goes a-walking into the woods, Amy wears a red hoodie like the well-known figure from fairytale—but she proves as good at cross-dressing in the Other’s costume as any antagonistic wolf in a grandma guise, blurring the line between man and woman, predator and victim. The gender divide that Felt shears is reflected in the fact that it has been co-written by Banker and Everson, collaborating to craft a work that can be worn interchangeably by male and female alike. It may well prove an uncomfortable fit for either sex, but is all the better for that. A dreamy, lyrical film that is also a nightmare, Felt proves that hell hath no fury like a man-woman scorned, while also advertising the fleshy realities beneath its hand-crafted fabric.